Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic

The title of this article is official, but it comes from a Japanese source.

If an acceptable English name is found, then the article should be moved to the new title.

| Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer | Nintendo |

| Publisher | Fuji Television Network |

| Platform | Family Computer Disk System |

| Release date | |

| Language | English[A] |

| Genre | Platform |

| Mode | Single player |

| Format | FDS:

|

| Input | Famicom:

|

| Serial code | FCG-DRM |

Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, usually referred to as simply Doki Doki Panic, is a Japan-exclusive platform game developed by Nintendo in cooperation with Fuji Television (who also published All Night Nippon: Super Mario Bros.) for the Family Computer Disk System to promote its event called Yume Kōjō '87 (translates to "Dream Factory '87").

The game was later released outside Japan in an altered format under the name Super Mario Bros. 2, since the original Japanese Super Mario Bros. sequel, Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels, was deemed too similar to the original and too difficult for overseas players. Eventually, the altered Super Mario–franchise version of Doki Doki Panic was released in Japan as well, under the title Super Mario USA, with its box art being a recreation of Doki Doki Panic's, with the Yume Kōjō characters replaced with Mario, Luigi, Princess Toadstool, and Toad.

Story[edit]

The game takes place inside a storybook. The book's story tells of the dream world of Muu, where the quality of dreams determines the quality of the weather the next day. Because of this, the Muu citizens invented a dream machine, so they could always have good dreams. One day, a mischievous being named Mamu (whose name was changed to Wart for Super Mario Bros. 2) invaded the land and used the dream machine to make nightmarish monsters. However, the Muu people learned of his weakness to vegetables and used them to defeat him.

The old storybook had found its way into the hands of a pet monkey, Rūsa, who gives the book to the young twins Poki and Piki. However, the twins quarrel and end up ripping out the last page of the book, causing its ending to be erased. Mamu, freed, reaches through the pages and kidnaps the twins, pulling them into the book. Rūsa gets the twins' parents, Mama and Papa, their brother, Imajin, and Imajin's girlfriend,[2] Lina, and they enter the book to rescue them.

Impact on the Super Mario franchise[edit]

The Doki Doki Panic engine started as a Super Mario–style tech demo using vertical-scrolling mechanics as opposed to side-scrolling mechanics.[3] Shigeru Miyamoto suggested the inclusion of side-scrolling mechanics to make it more of a Super Mario concept. Nintendo entered a licensing deal with Fuji Television, and the game's development proceeded with Yume Kōjō characters. Shigeru Miyamoto, as a result, was more involved with the development of Doki Doki Panic than he was in what eventually became the original Super Mario Bros. 2. Many of the game's enemies would become generic Super Mario enemies, though many were not intended to be that at the time of their creation. This includes Shyguys, Birdos, Pokeys, Bob-Ombs, Ninjis, and numerous others. Of particular note is how Mario, Luigi, Toad, and Princess Toadstool's skills and attacks have been shaped by the skills of the characters they replaced.

Some Super Mario elements had already been in place prior to the overhaul for America - both POWs (from Mario Bros.) and Stars (from Super Mario Bros.) are frequent and powerful items that serve the same purposes as in their games of origin.

Differences between Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic and Super Mario Bros. 2[edit]

Several changes were made in order to make the game appropriate for the Super Mario franchise. Graphical changes were made for certain enemies and characters. Additionally, the cream white Mouser boss featured in World 5-3 was replaced with Clawgrip. This change was in tune with the decision to release the edited Doki Doki Panic in place of the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2, which Nintendo of Japan feared was too hard for European and American gamers.[4]

Characters[edit]

- Imajin is the balanced character. While Mario replaces him, Imajin's balance in all areas has since become a staple of Mario's in many games where there are multiple playable characters.

- Mama has the ability to jump higher and lightly hover at the top of her jumps. Luigi takes her place as he had already had higher jumps than Mario in Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels. However, Luigi can jump slightly higher than Mama. Like his brother's balanced stats, his higher jumps have stayed in the Super Mario franchise.

- Lina can briefly hover, but she is low in speed and strength. Princess Toadstool replaces her. As a result of the license with Fuji Television expiring, Peach inherited Lina's floating capability, and the concept of Peach being able to float reoccurs in many video games. Games in the Super Smash Bros. series starting with Super Smash Bros. Melee (her first appearance in that series), as well as Super Mario 3D World, use similar mechanics to this game.

- Papa is the strongest character in the game and can run the fastest, though he is not very good at jumping. Toad takes his place, and while the idea of him being a strong character does not often reoccur in future video games (it is referenced in Wario's Woods and Mario Superstar Baseball), Toad being an especially fast character has since become a staple in games with multiple playable characters. Super Mario 3D World reincorporates the lacking jump.

- Poki and Piki are non-playable characters who get captured by Mamu at the beginning of the game and are rescued after his defeat. They are replaced by the Subcons in Super Mario Bros. 2, which are also present in Doki Doki Panic's endings.

- Rūsa is a non-playable monkey who gives Poki and Piki the old storybook that gets both kidnapped by Mamu.

Gameplay[edit]

- The player must beat the game with all four characters to view the ending in Doki Doki Panic, unlike Super Mario Bros. 2, where the player only needs to beat the game once to view the ending. However, due to Doki Doki Panic being on the Disk System, each characters' progress through the game was independently saved and could be returned to at a later date.

- A save feature is included.

- The player cannot run by holding the

button.

- Imajin, Lina, Papa, and Mama do not shrink when they have one hit point left.

- In Doki Doki Panic, knocked-out enemies cannot knock out other enemies as they proceed to fall off the screen, whereas in Super Mario Bros. 2, enemies can be comboed with careful throws.[5]

- It takes four hits for Mamu to be defeated in Doki Doki Panic, as compared to six in Super Mario Bros. 2; this is also present in the prototype version of Super Mario Bros. 2.

- An albino version of Mouser appeared as the boss of 5-3. In Super Mario Bros. 2, he was replaced with Clawgrip, who is the only boss exclusive to Super Mario Bros. 2.

- The type of Ninji that hops in place has three jump heights in Doki Doki Panic; Super Mario Bros. 2 only includes the low and high jump. Additionally, Ninjis may also jump with their hands down in Doki Doki Panic, whereas they always jump with their hands up in Super Mario Bros. 2.[6]

- The highest cloud platform in a section of 7-1 was removed, and the gray Snifit was moved onto a pillar where the cloud was once attached to.

- The shortcut in 6-3 is slightly different: in Doki Doki Panic, one can simply jump down from the cloud platform with the door; in Super Mario Bros. 2, two more cloud platforms stand between the door and the ground.

Visuals[edit]

- The title screen is entirely different.

- Rather than the storyline taking place in a dream world, it takes place within a storybook. The plot of the game is about two kids named Poki and Piki who fought over reading a book and ended up getting themselves pulled in by Mamu after accidentally tearing out the last page. A monkey known as Rūsa witnessed this and alerted the family.

- In Doki Doki Panic, the intro screens of the levels were actually pages from the storybook; levels were referred to as "Chapters", page number marks that were commonly used in story books appeared, and the intro screens lacked the location icons. In Super Mario Bros. 2, the intro screens were heavily edited to make them look like cards since Doki Doki Panic's story settings were from a storybook instead of a dream; the text "Chapters" was changed to "Worlds", the page number marks were completely removed, and location icons were added.[7]

- The characters and artwork are based on an Arabian-style theme.

- After leaving a key's home room, a Phanto inexplicably begins assaulting the player out of nowhere. In Super Mario Bros. 2, the Phanto now appears, albeit stationary and seemingly harmless, in the key's home room; however, once the key is retrieved, the Phanto comes to life and begins attacking.

- Shells replace the Big Face item, which were heads resembling blackface. They were edited due to the controversy over blackface mocking people of African ancestry.[8]

- Magical Potions were originally Magic Lamps. Magic Lamps were also present in the prototype version of Super Mario Bros. 2, as the Magical Potions were not implemented yet.

- Mushrooms were originally hearts.

- 1-Up Mushrooms were originally the heads of the character being controlled.

- Grass tufts were black instead of red.

- Mask Gates were originally generic masks instead of hawk masks.

- The explosion icon says "BOM" in Doki Doki Panic, and "BOMB" in Super Mario Bros. 2.

- Phantos originally had a less menacing appearance.

- Mushroom Blocks were originally various masks.

- Some vegetables looked slightly different.

- Cherries, POWs, vines, grass tufts, Crystal Balls, bomb fuses, water, cloud platforms, and spikes are still, unlike in Super Mario Bros. 2, where they are animated.

- Albatosses have only two frames of animation, while Super Mario Bros. 2 gives them eight (with only seven showing up outside of remakes due to a glitch).[9]

- Waterfalls and the fast quicksand animate faster than in Super Mario Bros. 2.

Sound[edit]

- The title screen music is completely different from that of Super Mario Bros. 2, which is an arrangement of the Super Mario Bros. "Underwater BGM". This title screen music would later serve as the basis for the ending music of Super Mario Bros. 2 when Mario is seen sleeping.

- Sound effects are changed, as the Disk System adds audio hardware not present in the NES.

- The Sub-Space music for Super Mario Bros. 2 is the overworld theme for Super Mario Bros., while the music for Doki Doki Panic is an Arabian theme.

- Super Mario Bros. 2 adds entirely new sections of music to the existing player select and overworld themes from Doki Doki Panic.

- Upon grabbing the Star, an Arabian-sounding tune plays in Doki Doki Panic, while the standard Super Mario Bros. Star fanfare plays in Super Mario Bros. 2.

- Most music tracks reused from Doki Doki Panic in Super Mario Bros. 2 sound slightly different from each other; the underground theme, for example, is slightly faster and lacks the bongo percussion in Doki Doki Panic.

Pre-release and unused content[edit]

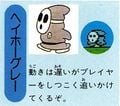

The game's manual lists a gray Shyguy, which does not appear in the game (despite the presence of gray Snifits). Its behavior is described as slowly pursuing the player. It appears to have been replaced with Tweeter, which is not listed in the manual; notably, World 4-3 features a Tweeter directly following a red Shyguy and a pink Shyguy, which may be a relic of this, and their internal object IDs have Tweeter in between the red and pink Shyguys. Tweeter does eventually turn to chase the player if on-screen long enough, as it is only programmed to do so if it is on the ground for long enough - thus its hopping extends that. Flurry is also missing from the manual and more directly chases the player, albeit at a fast speed and without hopping, so it may have also inherited some of its characteristics. Internally, Flurry (as well as Spark, which is also absent from the manual) have very large object IDs (appearing amongst bosses with complicated behaviors), indicating they were added very late in development (and thus after the manual screenshots were collected). In the manual for Super Mario Bros. 2, the gray Shyguy is removed while Tweeter, Flurry, and Spark are added.

Porcupo's manual sprite depicts it with feet, indicating it would have had a standard two-sprite walk animation rather than in the final, where it lacks visible feet and is animated by wiggling the segments on a single sprite. This image also appears in Super Mario Bros. 2's manual. Of note is that in the graphical data, Tweeter's sole sprite appears right after Porcupo's, which may suggest Porcupo's second sprite was overwritten by Tweeter late in development when it replaced the gray Shyguy.

Autobombs were originally going to shoot bullet-like shells rather than fireballs,[10] which is also part of their description in the manual. This statement is removed in the Super Mario Bros. 2 manual.

Staff[edit]

- Main article: List of Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic staff

Yume Kōjō '87[edit]

Doki Doki Panic was based on Yume Kōjō '87, an event sponsored by Fuji TV and held from July 18th to August 30th, 1987. On the last day of this event, there was a grand finale.[11] This finale was meant to introduce a new generation of media that would arrive in the years to come, with various technical displays, as well as to advertise Fuji TV's fall lineup of shows. Elements from the event carried over to the game include the characters of Papa, Mama, Imajin, Lina, Poki and Piki, the blimp on the title screen, and the use of masks as a visual motif.

Gallery[edit]

- For this subject's image gallery, see Gallery:Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic.

Multimedia[edit]

- For the complete list of media files for this subject, see Multimedia:Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic.

| File info |

References in later media[edit]

- During the Super Mario USA adaptation, Princess Peach, trapped in Sub-space, finds a Magic Lamp from Doki Doki Panic. Birdo states it is useless and instead pulls out its Super Mario Bros. 2 equivalent, the Magical Potion.

- On Toad Harbor, there is a sign saying "Shy Guy Metals: Since 1987", referencing this game's release date and the introduction of the Shy Guys.

- The trophies for Birdo and Shy Guy mention that they actually debuted in Doki Doki Panic (the Yume Kojō part of the title is not mentioned in English versions).

- During her concert in Plum Park, Birdo sings the line "two hearts in doki doki panic," referencing this game's title.

- One of the terms Bob-omb uses to refer to his amnesia is "Thinky Thinky Panic", referencing this game's title, which was where Bob-ombs were first introduced.

Names in other languages[edit]

| Language | Name | Meaning | Note(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panikku |

Yume Kōjō means "Dream Factory", while doki doki is Japanese onomatopoeia for a rapidly beating heart and panikku is a transcription of the English "panic", so in effect, it can be translated as "Dream Factory: Heart-Pounding Panic". | [12] | |

| Italian | Dream Machine: Doki Doki Panic | - | [13] | |

| Portuguese (Brazilian) | Yume Koujou: Doki Doki Panic | - | [14] |

Notes[edit]

- The coin counter in Bonus Chance segments is displayed in hexadecimal. When the player gets more than nine coins in a level, letters from A to F are used instead.

- Coincidentally, some promotional material features Imajin and Lina posing with Mario and Princess Peach, their eventual replacements in Super Mario Bros. 2.[15]

- A possible reason why the game has seen no re-releases outside of Super Mario Bros. 2 is because the rights of Yume Kōjō, along with its characters, like Imajin, are owned by Fuji TV.

Footnotes and references[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Contains some Japanese words.

References[edit]

- ^ 夢工場ドキドキパニック. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved May 19, 2025 from Media Arts Database. (Archived June 24, 2021 via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Gaijillionaire (July 17, 2016). Yume Kojo! Not The Story of Super Mario Bros 2 vs Doki Doki Panic Nintendo NES History Fuji TV | Gテレ (08:38). YouTube (English). Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (April 1, 2011). The Secret History of Super Mario Bros. 2. Wired (English). Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ NintenDaanNC (December 7, 2010). [NC US] Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary - Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto #2. YouTube (English). Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Shesez (February 11, 2022). ALL Differences Between Mario 2 and Doki Doki Panic - Region Break (34:00). YouTube. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Looygi Bros. (March 1, 2025). 20 Cool Differences between Super Mario Bros. 2 and Doki Doki Panic (4:55). YouTube (English). Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ VCDECIDE (October 18, 2015). Regional Differences [04] Super Mario Bros. 2 vs Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic (Nes vs Famicom). YouTube (English). Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ TCRF. Super Mario Bros. 2 (NES)/Regional Differences § Koopa Shells. The Cutting Room Floor. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ TCRF. Super Mario Bros. 2 (NES) § Eighth Animation Frame. The Cutting Room Floor (English). Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Prerelease:Yume Koujou: Doki Doki Panic. The Cutting Room Floor. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Gaijillionaire (July 17, 2016). Yume Kojo! Not The Story of Super Mario Bros 2 vs Doki Doki Panic Nintendo NES History Fuji TV | Gテレ (17:11). YouTube (English). Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Japanese box art

- ^ Andrea Minini Saldini (July 2002). Nintendo La Rivista Ufficiale Numero 2. Milan: Future Media Italy SpA (Italian). Page 90.

- ^ Nintendo World Number 119. Brazil: Nintendo (Portuguese). Page 27.

- ^ Mackie, Drew (June 21, 2023). Why Is Super Mario Bros. 2 Missing a Level?. Thrilling Tales of Old Video Games (English). Retrieved June 23, 2024.

External links[edit]

- "From Doki Doki Panic to Super Mario Bros. 2" on The Mushroom Kingdom

- Japanese Wikipedia page