The 'Shroom:Issue LXVII/A History of Video Games

You unlock this door with the key of history. Beyond it is another dimension —a dimension not only of text and images, but of mind. It is a journey into a wondrous land where legendary developers and artists shape an industry of imagination. That’s your signpost up ahead. Your next stop: the Toad Zone.

Hey y’all, this is your resident gaming historian Toad85 here ripping off Rod Serling to kick off my 12th ‘Shroom article. You know, when I browse around the internet, I’m surprised at how many people overlook the portable market when discussing gaming events. Or if they do remember, they only focus on one series (like Kirby or Pokemon) or quickly write it off. In reality, the handheld console market was much more competitive than most gamers know. If events had gone just a little bit differently in any direction, we could be seeing an entirely different market in the present, and some of our favorite games would never have existed. It almost reminds me of Sterling’s 1959 romp through another realm, and how just a teensy thing off kilter could frighten a generation of TV watchers.

So, to kick off the fall, I’ll be discussing how Nintendo, Atari, and Sega went head-to-head for the hearts of your hands.

CONSOLE WARS: THE PORTABLE WARS

Well, first thing’s first, let’s discuss the first handheld for a bit.

The first all-digital handheld electronic game produced was Mattel’s Auto Race, a 1976 LCD racing game. The player’s car (a dashed line) must make it to the top of the screen 4 times (4 laps) to win, but in order to do so, they must swerve past other dashed lines and avoid wrecking. It’s simplistic, but it’s 1976, so what do you expect.

In 1979, Gunpei Yokoi introduced the Game And Watch, a device that functioned both as a clock and as an LCD game console. The Game And Watch featured decent graphics, considering the technology it was using, and was a moderate success. Unfortunately, though, the system only played one game; if you wanted another Game And Watch title, you had to buy another system. Several advances that would eventually become the norms in gaming were actually first seen in the Game And Watch series: the modern D-Pad was introduced in Donkey Kong; the double-screen that made the DS famous in 2004 was what made Donkey Kong II unique in 1983; Squish featured two distinct gameplay modes that were radically different from one another.

Perhaps the closest precursor to a true 80’s handheld console, though, was Milton Bradley’s Microvision. Produced around the same time as the Game And Watch, the Microvision was the first handheld to use interchangeable cartridges, and utilized technology typically reserved for home consoles. Unfortunately, the Microvision was a financial flop, mostly due to poor marketing and a lack of a “must-buy” game. By 1981, Milton Bradley had moved onto other projects.

However, these three did popularize the idea of gaming on the go, and companies like Tiger Electronics became famous off of their LCD exploits. Cut to 1989, and Nintendo and Atari both happen to be working on a new cartridge-based portable gaming system.

Let’s discuss Atari’s gizmo first. The Atari Lynx was conceived by an independent hardware manufacturer named Epyx, but Epyx didn’t have the money to release the console by itself. So Atari was called in, they made some tweaks, and slated release for 1990. The Lynx sported all-color 8-bit graphics, a backlit screen, and a powerful engine running the show. At first glance of the system, you’d swear you were playing a really tiny NES.

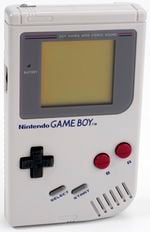

Gunpei Yokoi’s Game Boy, on the other hand, was sticking with an LCD screen and simple hardware to keep design costs down. What Nintendo did have an advantage over Atari in, though, was price. While the Lynx was scheduled to retail at $199, the Game Boy cost almost half that. Plus, Nintendo had much more name recognition; remember, Atari still hadn’t lived down their ’83 Crash reputation. Despite having the superior console, Atari was the one fighting the uphill battle.

The handheld market should have been tighter than it was. You’ve got the all-powerful color portable system with great graphics and sound versus the little-system-that-could with the black and green screen, cheap price and great battery life. Ultimately, the victor had to be the system with the better games. While the Lynx did have some quality titles, like Chip’s Challenge and Joust, the Game Boy’s library blew Atari and Epyx out of the water. You’ve got Super Mario Land, Dr. Mario, Mega Man, Batman, and a whole crap ton of other well-received games to choose from. But the crown jewel of the Game Boy was its pack-in game: Tetris. A fairly popular Soviet game designed by Alexey Pajitnov, Tetris was unearthed by Nintendo of America President Minoru Arakawa at a 1988 arcade expo. Obsessed with the game, he decided it would be perfect for the still-in-development Game Boy.

However, because the Cold War still hadn’t ended, Arakawa had a bit of trouble securing the rights to publish Tetris. And Arakawa wasn’t the only one gunning for Russia’s brick busting technical marvel; Atari, Sega, and Proof Software were also attempting to purchase the license to sell Tetris. In the end, the Russian government just decided to divide up the Tetris license depending on how each company planned to release their version. Atari was granted the right to port it to home consoles, Proof Software was given the brand for use in Japan, and Nintendo was allowed to produce copies of Tetris for handheld consoles like the Game Boy.

With the help of Tetris, Game Boys sold at a frightening rate. Within two weeks, Nintendo had sold through its entire stock of 300,000 units. By the end of 1990, that number had reached numbers that took the NES three years to top.

But Nintendo’s problems weren’t over yet. Sega began developing its own color handheld, the “Game Gear”, late into 1989. Sega had a bit of an edge over Atari for one reason: while Atari had failed due to a lack of good, original games, Sega was the new, “cool” kid on the block with a heap of new ideas and franchises to milk. Much like their strategy with the Genesis, Sega was marketing the Game Gear as doing everything the Game Boy couldn’t. To combat the Game Boy’s “creamed spinach colored” screen, the Game Gear was essentially a portable Master System. While the Game Boy’s bulky shape made it wearisome for users to hold for extended periods of time, the Game Gear was streamlined and fit a gamer’s hand comfortably. The Game Boy lacked a color screen, so Sega plopped one into the Game Gear. With a North American release date set in 1991 and a reasonable price of $149, Nintendo had good reason to be spooked.

Fortunately for Nintendo, though, the Game Gear was a dud. How, you may ask? There are three main reasons. Perhaps most importantly, the Game Gear appeared a full two years after the Game Boy. That’s a lot of ground to lose, and without a must-buy title the like of Tetris, the Game Gear couldn’t drive any stake into the handheld market vampire. Sega’s second slip up concerned its eco-friendliness. To put it bluntly, its battery life sucked. Six batteries were needed to make the system run, and that only lasted four hours. If you wanted your Game Gear for a long car ride, you’d better bring an extra set of double-A’s.

But the biggest reason for the Game Gear’s downfall, and what would doom countless other consoles and portable devices, was a complete dearth of third-party support. While Sega did churn out some fine titles, a system can’t last if there isn’t a quasi-constant stream of quality games to back it up. By the mid-‘90s, just as the Poké-craze was heating up, the Game Gear was officially discontinued. The Game Boy and its successors would maintain almost a monopoly on the portable gaming market until the PSP’s release in 2005.

Now, what if Sega and Atari had not taken the fall? Would we see a greater parity of handheld classics? Would the technology of handheld devices be much greater than what the PSVita and 3DS currently offer? Would some of our favorite games and series, like Pokémon, Kirby, and Professor Layton, ever had seen the light of day? Or if they did get the green light, how different would they be? How much would our gaming libraries be changed if the Lynx and Game Gear had been successes while the Game Boy line bit the dust?

Imagine it: a world with no Game Boy. That means 118 million less pieces of metal and plastic formerly lining pockets around the world. That also means $10.7 billion less in revenue generated by Game Boy sales, plus $12.1 billion for the Game Boy Advance. Combined, that’s more than NASA’s entire space budget! And that’s not even mentioning all the money Nintendo made selling first-party games to play on those trinkets. If Sega and Atari had been able to capitalize on all the profit to be made in Nintendo’s absence, dude, what would happen?

Anything’s possible in the Toad Zone.

I’m Toad85, your resident gaming historian, and what’s the way it could have been?