The 'Shroom:Issue LXI/A History of Video Games

Hellooo, it’s Toad85. I don’t remember it, so you have to.

It is now 1981. Reagan has just been sworn in as president. The space shuttle program is now underway. The Pope has been shot. And Nintendo, perhaps most importantly, is trying to make it big in the video game market in North America.

However, Nintendo was not the video game colossus it is today, with people buying their consoles and games simply because they made it. Nope, Nintendo products were a hard sell, especially in the saturated market of the early 80’s (see my “Video Game Crash of 1983” article from December). Nintendo had already tried to break into the American market, but had ultimately failed. Multiple times. But this article is not about their failures.

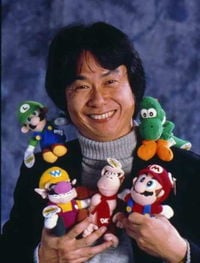

Instead, we shall speak of the man who pretty much saved Nintendo’s butt, and his industry-changing game.

PART THREE: SHIGERU MIYAMOTO AND DONKEY KONG

Not all Japanese video game companies, mind you, were a flop in America. Japanese companies like Taito and Namco successfully broke the American video game market, and arcade games as a whole tended to be hits on both sides of the Pacific. OK, so then why couldn’t Nintendo do the same?

For one thing, Nintendo didn’t really have a ground-breaking game to build off of. Namco had Pac-Man, and Atari had Pong, but Nintendo had… Radar Scope?

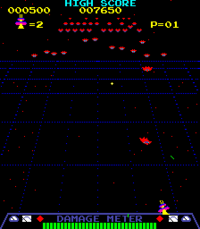

Yes, Radar Scope. An early cabinet arcade game, Nintendo thought that this would be their ride to the top. It was similar in a way to Galaga, in that you shot little rectangles at weird-looking alien ships. However, probably because the U.S. market was already saturated with space shooters, Radar Scope never made a dent overseas. Only 1,000 or so cabinets were sold in total, and Nintendo failed to make any kind of profit.

Enter Shigeru Miyamoto. A young college student, Shigeru had just graduated with a degree in industrial design. Hiroshi Yamauchi (remember him?) brought in the student to convert the unsold Radar Scope cabinets into a new game. This new game would be geared towards American audiences, and hopefully put Nintendo on the map, but would need to stay under Nintendo’s budget of $100,000 (Roughly $250,500 in today’s currency.) This was not a lot of money to work with, but Miyamoto was up to the task.

At first, Nintendo pursued a license from the “Popeye” comic strip. However, the license fell through, and Nintendo decided to continue making the game with its own characters. This provided Miyamoto with an interesting situation, and he became the first developer to craft a story for his game.

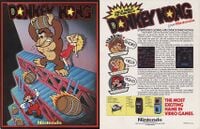

The story went something like this. Jumpman, whose name derives from his primary defensive move, as well as the suffix -man (Miyamoto wanted something to the effect of “Pac-Man”), owns a pet gorilla named Donkey Kong (whose name stems from synonyms for “stubborn” and “ape”). However, Donkey Kong grows resentful of his master and kidnaps his girlfriend, taking her to the top of a construction site. The carpenter Jumpman must scale the 100-meter tall building in order to rescue Pauline.

Okay, it’s no masterpiece. But it did set a standard for storytelling in a video game. This was the first time a story had been played out onscreen, you know.

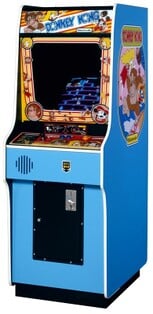

Hiroto Yamauchi could not have been more thrilled with Miyamoto’s work, entitled after the villain, and had high hopes for the product. The game had four screens, compared with the typical arcade game’s one, and used about 20,000 lines of code. Gunpei Yokoi came up with an idea to make seesaws in certain levels that would catapult Jumpman across the screen; these would become springs instead. At first, there were some concerns that Donkey Kong deviated too much from the traditional maze and shooter arcade games, but Miyamoto, Yamauchi, and President of Nintendo of America Minoru Arakawa quickly quelled these queries. Donkey Kong was ready for export.

During export, though, there were a few changes. Mario Segale was upset with Arakawa, who could not keep up with the rent, but was promised that the money would come soon. Segale became the namesake for Jumpman in America; partly out of compensation, partly because he looked so much like the character. Jumpman’s girlfriend would be named Pauline, after the wife of warehouse manager Don James. The new names were to be printed on the cabinet instead of “Jumpman” and “Lady.”

Arakawa decided to sell the new game to two bars in Seattle, coincidentally mirroring Pong’s first sale to bars in California. The managers initially showed reluctance, but soon flipped their opinions when they saw Donkey Kong raking in 120 plays a day. The owners ended up asking for more machines. This was a big outcome for a company that couldn’t afford their own warehouse, and Donkey Kong soon went national.

Sales of Donkey Kong grew like wildfire, and because Nintendo was making them out of the unsold Radar Scope machines, Nintendo was making much more money than they were spending. Eventually, Donkey Kong was selling so well that Nintendo had to build its own machines to keep up with demand. All in all, over 67,000 Donkey Kong machines were sold in the U.S., Japan, and Canada. Nintendo had gone from penniless to filthy rich in just a matter of months. Lawyer Howard Lincoln, expecting to hear a call from Nintendo about filing for bankruptcy, instead got a call asking him to “protect Nintendo’s newfound fortunes.”

But not all was well in the world of Nintendo. In 1982, Nintendo was sued by film giant Universal Studios, who claimed that the name “Donkey Kong” infringed on their copyright holding of “King Kong.” So what did Nintendo do in response? Well, I’m kinda out of room here, so tune in next time, please!

Again, I’m Toad85; I don’t remember it, so you have to!